As high resource-consuming and high uncertainty are two most critical challenges to radical innovation, it is imperative to adopt resource structuring for an active management of their resource portfolios, and also to adopt strategic flexibility for an active management of their contextual uncertainties, especially for firms in the emerging economies characterized by serious resource deficiency and high contextual uncertainty. Though firms engaging in resource structuring and strategic flexibility separately could foster radical innovation, the interaction effect of resource structuring and strategic flexibility could be complementary or substitutive, and the effective utilization of these two organizational dimensions as a joint force should be well aligned to achieve scientific breakthroughs.

High uncertainty can be characterized on three core dimensions:

(1) The dimension of complexity with diverse elements interconnected in a holistic pattern;

(2) The dimension of dynamism with fast changing elements in a discontinuous pattern;

(3) The dimension of scarcity with limited resources available in a constrained pattern.

Rooted in the above three dimensions, high uncertainty renders radical innovation more salient than in the context of high certainty. Further, these three dimensions of high uncertainty make resource structuring more salient than in the context of high certainty. Finally, these three dimensions of high uncertainty require strategic flexibility as more salient than in the context of high certainty.

1. The research on resource management frames resource structuring as managing a firm’s resource portfolio in a dynamic process, and it suggests that the core mechanisms to restructure resource portfolios fall into two categories:

(1) Resource acquiring, refers to the active management of a firm’s resource portfolio. Resource acquiring can provide a firm with the externally available advanced knowledge that may lead to a new technological trajectory. Hence, resource acquiring represents a favorable channel to transfer intangible assets for innovation. Also, resource acquiring helps expand the scope of information search beyond what is directly available within a firm. The infusion of new information from the external sources tends to generate the benefits of recombining the existing ideas and also getting access to novel ideas, both necessary for radical innovations.

(2) Resource accumulating, refers to developing resources from internal sources, which tends to enable the expansion of a firm’s internal resources. Resource accumulating can strengthen the existing resource portfolio that enhances the isolating mechanisms, as the basis for a firm’s competitive advantages from the perspective of the resource-based view. Further, such a resource portfolio also serves as the basis for a firm’s core competence. Because accumulated resources are deeply embedded in organizational routines over time, they cannot be easily traded and redeployed outside the firm. Firms can effectively extend the scope of internal resources by broadening the boundaries of their core competences, which provide the sufficient foundation for resolving complex or unusual problems.

Resource acquiring can provide the necessary resources that firms may not be able to develop internally due to time diseconomies (a lack of time) or learning constraints (a lack of absorptive capability). However, the market is unlikely to provide a firm with all required resources, which makes resource accumulating necessary, especially for the development of core competence. Hence, it appears reasonable to argue that both resource acquiring and resource accumulating are often necessary as two core mechanisms of resource structuring for a typical firm to build its sustainable competitive advantage. On the one hand, these two mechanisms are similar in some aspects, such as requiring firms to identify resource needs and also invest in the development of needed capabilities, especially for fostering radical innovation. On the other hand, these two mechanisms are distinctive in other aspects, such as providing different kinds of resources for radical innovation. It is worth noting that the two mechanisms of resource structuring are related to the two mechanisms of innovation in terms of open and closed innovations. In particular, the interplay between the two mechanisms of resource structuring can be expected to play the most critical role in the development of competitive advantages in the resource domain as theorized by the resource-based view.

2. Strategic flexibility, as a special type of organizational capability for a firm to reallocate and reconfigure its organizational resources, processes, and strategies to manage environmental changes, represents the management of contextual risk and uncertainty by promptly responding in a proactive or reactive manner to market opportunities or threats. A firm with strategic flexibility can reduce the response time to dynamic changes, and enable the more effective redeployment of resources, thus enhancing the value of resources for innovations.

Sanchez suggests that strategic flexibility “depends jointly on the inherent flexibilities of the resources available to the firms and on the firm’s flexibilities in applying those resources to alternative courses of action”, thus falls into two capabilities.

(1) Resource flexibility, is defined as the special capability of identifying and acquiring the use of flexible resources that can offer strategic options for a firm to pursue alternative courses of action in responding to the shifts in its competitive context. Resource flexibility is primarily concerned with the technical capability to switch between different applications of a specific resource for specific tasks (thus mostly about the technical characteristics of any specific resource). It has three dimensions about the flexible use of resources: a. the range of alternative uses for a resource; b. the cost and difficulty of switching from one use of the resource to another use; c. the time required to switch from one use of the resource to another.

(2) Coordination flexibility, is defined as the special capability of coordinating the use of resources to maximize the flexibilities inherent in the resources available to a firm. Coordination flexibility focuses most on the organizational capability to switch between different applications of diverse resources configured or bundled in a portfolio, especially the critical link between internal and external resources, for any complex tasks . It also has three dimensions: a. the ability to define the uses to which a resource can be applied; b. the ability to configure a resource portfolio for a targeted use; c. the ability to deploy resources through organizational systems and processes for a targeted use.

The value of strategic flexibility is particularly salient for the inherent risk and cost of radical innovation as critical challenges to firms in a highly dynamic context. Although both resource flexibility and coordination flexibility are concerned with the risk, cost and time related to identifying, configuring, and deploying a bundle of resources, the two types of flexibility differ in their specific focuses, with resource flexibility focusing on the technical properties of a specific resource in terms of a range of its use, while coordination flexibility on the organizational properties of a resource portfolio as a whole in terms of defining (identifying) and configuring (structuring) resource portfolios through organizational systems and processes.

Because of different characteristics, resource flexibility and coordination flexibility have different roles in radical innovation, so they are expected to associate with different mechanisms of resource structuring. In sum, the two core capabilities of strategic flexibility are both necessary for a firm to engage in radical innovation, but each has its own distinctive strengths and weaknesses, all of which will be made more salient by the special context of high uncertainty.

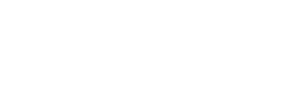

3. The matching perspective stresses the joint effect of multiple factors, and suggests that the independent or separated effect of each factor alone would be insufficient to explain the complex links between such factors, while the matched effects could be complementary or substitutive. Accounting for all potentials for value creation with multiple factors, the matching theory intends to utilize the complementary links among such factors so as to maximize joint value creation. From the matching perspective, we argue that the primary mechanisms of resource accumulating and resource acquiring are not mutually exclusive in absolute terms, nor are the capabilities of resource flexibility and coordination flexibility. Figure 1 shows the interaction between resource structuring and strategic flexibility.

Figure 1 The Interaction of Resource Structuring and Strategic Flexibility

Contributions:

(1) We have advanced the extant research on resource management by interconnecting resource structuring with strategic flexibility for their distinctive interaction effect on radical innovation under high uncertainty. Advancing the extant research in resource management with a focus on the role of resource structuring, we argue that resource structuring alone is insufficient for radical innovation under high uncertainty, and resource structuring as a type of strategic mechanism must be enabled by strategic flexibility as a special type of strategic capability. Our unexpected finding about the negative interaction effect between resource accumulating and coordination flexibility implies that they tend to be incompatible, thus often mismatched. This finding has the potential to enrich the research on organizational inertia and core rigidities. Second, this article has advanced the extant research on organizational capability by interconnecting strategic flexibility with resource structuring for their special interaction effect on radical innovation under high uncertainty. Again, our unexpected finding concerning the negative interaction effect between resource acquiring and resource flexibility implies that they are incompatible, thus mismatched. This surprising finding has the potential to enrich the research on absorptive capability. In general terms, the effectiveness of resource acquiring will depend upon absorptive capability as the special capability to learn from external sources. The explanations for the substituting, rather than complementary, links between resource acquiring and resource flexibility, may lie in the reduced positive effect of technical diversity due to a narrowly focused absorptive capability, which may not counterbalance the negative effect of core rigidity, or even reinforce each other in a vicious cycle. In other words, the lack of open and broad capability to absorb diverse resources could worsen core rigidity. Both contributions are based upon the hidden links between resource structuring (as a type of resource configuration mechanism for dynamic resource bundling) and strategic flexibility (a type of organizational capability to manage dynamic context) in terms of their complementing and substituting roles in different aspects, which are especially salient in the special context of high uncertainty. In short, our findings provide a more nuanced and insightful view about how strategic flexibility and resource structuring jointly shape radical innovation: both of them are needed, especially their interaction under high uncertainty, but such interaction must be properly matched. Our perspective provides not only extensions of resource management research, but also a novel explanation for the conflicting findings about the critical link between resource and innovation. Further, this perspective sheds light on the interaction between specific types of strategic capability and strategic mechanism by suggesting that the resource-based view and knowledge-based view could be integrated with the process-based research on strategic issues (e.g., strategy as practice; the behavioral approach to strategy). This study contributes to the literature of strategy by providing a new concrete avenue for the paradigm shift in strategy research from the old focus on static content to the new focus on dynamic process, as advocated more than three decades ago.

(2) Practically, our findings offer managers with some useful implications about how to effectively engage in radical innovation under uncertainty, which are typical in the emerging economies like China. First, the findings about the matched interaction between the two mechanisms of resource structuring and the two capabilities of strategic flexibility inform managers that they should leverage the right mechanisms with the right capabilities. Though firms engaging in resource structuring and strategic flexibility separately could foster radical innovation, such an approach is not effective under high uncertainty. Second, managers should pay attention to simultaneously utilize the matched mixes of both mechanisms of resource acquiring and resource accumulating as well as both capabilities of resource flexibility and coordination flexibility, rather than just one pair at a time.